Hungry and disoriented because of an unseasonably warm winter, some unwanted creatures are invading backyards in Arizona. Look out for scorpions.

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — The scorpions that scurry around this desert region emerged from their winter slumber early this year.

Usually dormant until late March, the creatures came out in February as temperatures soared, making a month that is generally pretty pleasant the second-warmest February on record.

That got Ben Holland’s phone ringing: Callers were finding scorpions on their beds, in their showers, on walls in and outside their homes and all over their yards. Mr. Holland — a vice president for digital marketing by day, a scorpion exterminator by night — assembled his band of hunters, young men in or just out of college, and put them to work.

“Our approach is population control,” said Mr. Holland, 32, who started Scorpion Sweepers in 2006, putting to use his experience collecting scorpions for a laboratory while in college and his once-ignored biology degree. “We don’t poison the scorpions. We don’t smash them. We pick them up one by one.”

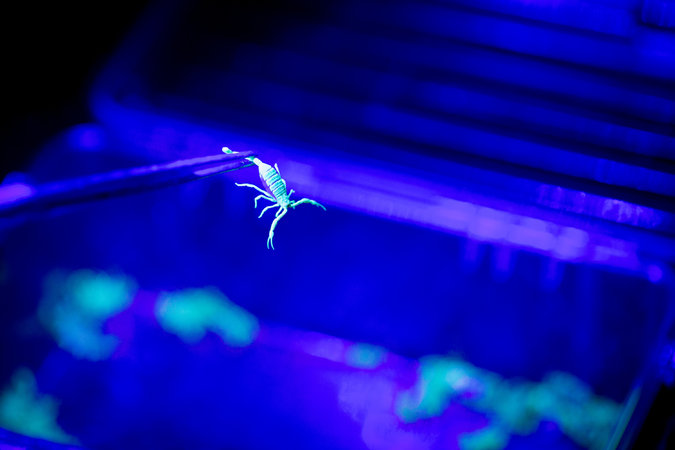

They use a tool called a forceps, which looks like the tweezers one might use to pluck eyebrows, only bigger. Success requires speed and dexterity, skills that are learned on the job. On his second season, Toby Riley, 24, whose other career is in graphic design, demonstrated it as best as he could to Zach Wilson, a scorpion-hunting rookie three weeks shy of graduation from Arizona State University. (Major: digital marketing.)

“Pinch the scorpion’s tail and turn your wrist, like this,” Mr. Riley said, moving his lower arm as if hurriedly scooping beans from a pot.

Pest extermination is big business in these parts and specialties vary — from African bee catchers to termite killers and roof-rat snatchers. Mr. Holland and his sweepers go after scorpions only, and they work only after dark.

Last week, Mr. Riley and Mr. Wilson were zigzagging along manicured grass and river rocks here on a moonlit night — “one acre out front, one acre out back,” the homeowner, a lawyer named John Schill, told them. Water trickled from a three-tiered fountain. Dogs barked inside. A palm tree leaned above the pool, its trunk twisted into a sideways “s.”

Mr. Riley and Mr. Wilson buttoned their shirt collars snug against their necks (to keep bugs from falling in), slipped on thick neoprene gloves, laced up their snake-proof boots and turned on the big black lights they each carried.

Scorpions glow under black lights. The glow comes from a substance found inside a hard-and-thin coating on the scorpion’s exoskeleton. Scientists are not sure what purpose it serves. Some say it is to confuse prey; others believe it is to protect scorpions from sunlight.

There are 1,800 types of scorpions in every place on the planet except for the Arctic, and more than 50 species in the Sonoran Desert, which covers much of the state. At no more than three inches long, bark scorpions are the smallest, most common and most dangerous — “the only one of them considered to be life-threatening,” said Keith Boesen, director of the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center, housed at the University of Arizona College of Pharmacy in Tucson.

On average, the center and its counterpart in Phoenix log 12,000 reports of scorpion stings each year, though many more go unreported because people treat them at home. Children, older adults and those who are infirm are particularly vulnerable and should seek immediate help if they get stung, Dr. Boesen said. Deaths are rare — there was one in 2013 and another some 10 years earlier, he said.

Still, pain and discomfort from a scorpion’s sting are inevitable and the reactions can range from scary to bizarre.

Israel Leinbach, a biologist for the United States Department of Agriculture in Hawaii who spent years in Phoenix researching bark scorpions, described the pain as “the feeling of being stabbed with a hot knife.” It may last anywhere from a few hours to several days and resist all efforts to make it go away quicker: cold compresses, over-the-counter pain medication, antihistamine.

One’s face and tongue might feel numb, but there is no treatment for numbness, Dr. Boesen said. And it could get worse. Because venom is a neurotoxin, nerves could fire uncontrollably. Muscles may spasm. Lips might twitch. Sometimes, eyes will roll around, in opposite directions.

“It almost looks like you’re possessed,” Dr. Boesen said.

Unlike rattlesnakes, scorpions have no warning system, and bark scorpions, in very light shades of brown, can be particularly hard to see. Like rattlesnakes, though, scorpions will sting only if they feel threatened — and a threat can amount to as much as a foot sliding inside a shoe, a scorpion’s favorite hiding spot.

Another are the crevices on stucco walls, a staple of homes built in these parts. Mr. Leinbach calls them “scorpion hotels.”

Scorpions are ultimate survivors, having evolved during their estimated 400 million years on this planet to withstand inhospitable conditions such as those they find in the desert.

Until they find a home at somebody’s home, that is.

Mr. Schill’s had plenty of moisture on the ground, as sprinklers wet his grass and 149 palm trees every night. The moisture attracts bugs — food for the scorpions. The palm trees’ flaky bark provided perfect hideaways. Mr. Riley plucked five scorpions from a single one of those, 107 scorpions after 90 minutes of crouching and leaning forward to snag the critters. Scorpions that are not distributed to research labs are killed “in the most humane way possible,” Mr. Holland said. (Freezing them is an option.)

Many of them scurried away, slipping under river rocks and the ceramic tiles on the roof.

“I’m not worried,” Mr. Riley said, holding a plastic box filled with his loot for the night. This was their first visit (cost: $200 to $250, depending on the property size and location). He knew that to bring the infestation under control, there would have to be more visits.

“Scorpions are territorial,” he added. “I’ll know exactly where to look for them next time we come back.”